Muhammad

bin Tughluq (1325 -

1351). Ghiyasuddin was succeeded by his

son Prince Juna khan, Fakhuruddin Muhammad the title of Muhammad Tughluq, in

1325 AD. Sultan had applied to the Abbasid Caliph Al – Hakim II (42nd Caliph of

the Abbasid Caliphate in

The token currency, 1330 A.D. Muhammad-bin-Tughluq has rightly been called the

prince of moneyers. One of the earliest acts of his reign was to reform the

entire system of coin age to determine the relative value of the precious

metals and to found coins which might facilitate exchange and form convenient

circulating media. But far more daring and original was his attempt to

introduce a token currency. Historians have tried to discover the motive which

led the Sultan to attempt this novel experiment. The heavy drain upon the treasury

has been described as the principal reason which led to the issue of the token

coins. It can not be denied that a great deficiency had been caused in the

treasury by the prodigal generosity of the Sultan, the huge expenditure that

had to be incurred upon the transferred of the capital and the expeditions

fitted out to quell armed rebellions. But there were other reasons which must

be mentioned giving an explanation of this measure. The taxation policy in the

Doab had failed; and the famine that still stalked the most fertile part of the

kingdom, which is the consequent decline in agriculture, must have brought

about a perceptible fall in revenue of the state. It is not to be supposed that

the Sultan was faced with bankruptcy; his treasure was not denuded of specie

for he subsequently paid genuine coins for the new ones, and managed a most difficult

situation with astonishing success. He

wished to increase his resources in order to carry into effect his grand plans

of conquest and administrative reform, which appealed so powerfully to his

ambitious nature. There was another reason; the Sultan was man of genius who delighted in originality and loved experimentation. With the examples of the Chinese and Persian rulers before him, he decided to try the experiment without slightest intention of defrauding or cheating his own subjects as is borne out by the legends on his coins. Copper coins were introduced and made legal tender; but the state failed to make the isue of the new coins a monopoly of its own. The result was, as the contemporary chronicler points out in right orthodox fashion, that the house of every Hindu of course as an orthodox Muslim he condones the offences of his coreligionists was turned into a mint and the Hindus of the various provinces manufactured lacks and crores on coins. Forgery was freely practiced by the Hindus and the Muslims; and people paid their taxes in the new coin and purchased arms, apparels and other articles of luxury. The village headmen, merchants, and landowners suppressed their gold and silver, and forged copper coins in abundance, and paid their dues with them. The result of this was that the state lost heavily while private individuals made enormous profits. The state was constantly defrauded for it was impossible to distinguish private forgeries from coins issued by the royal mint. Gold and silver became scarce; trade came to a stand-still and all business was paralyses. Great confusion prevailed; merchants refused to accept the new coins which became as “valueless as pebbles or potsherds.” When the Sultan saw the failure of the scheme, he repealed his former edict and allowed the people to exchange gold and silver coins for those of copper. Thousands of men brought these coins to the treasury and demanded gold and silver coins in return. The Sultan who meant no deception was considerably defrauded by his own people, and the treasury was drained by these demands. All token coins were completely withdrawn and the silence of Ibn Batuta who visited |

Tuesday, 6 January 2015

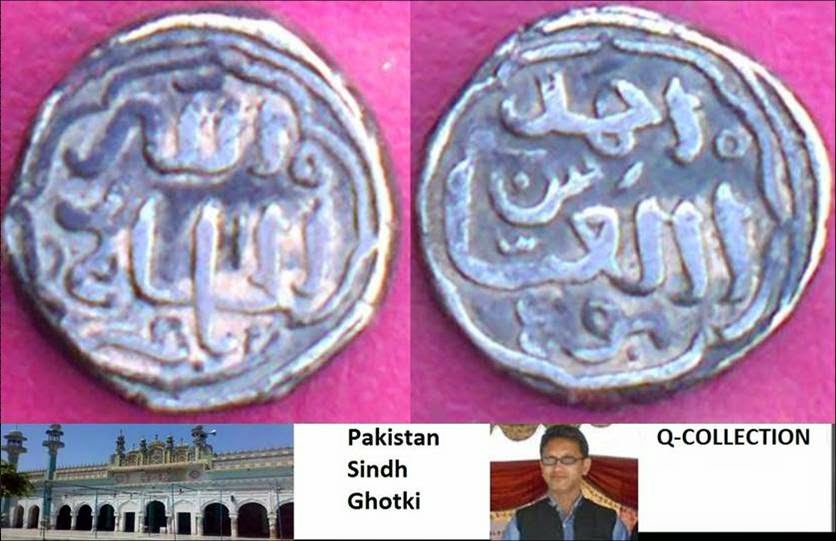

Delhi : Muhammad bin Tughluq , 1325 – 1351 A.D. Silver coin 32 rati.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Disclaimer

This Blogspot and its Contents are Original 2011-2013, Abdul Qayoom Dayo and coinsrevolution.blogspot.com & we drive thousand of visitors Traffic in web blog and The material and information contained in this website are provided as without any warranty of any kind,

Welcome to Q-Collection

We can say Welcome to Main page and Thank You in a way that they will always remember that you appreciated and useful Information on British coins, World Coins, Khushan Empires, America, Mughals, Indo Greek, and other coins worth money for more collector

No comments:

Post a Comment